This blog was originally posted on the NRDC website on September 10, 2020.

Written by David Goldstein, Energy Co-Director at NRDC and New Buildings Institute Board President, and Kevin Carbonnier, Project Manager at New Buildings Institute.

Achieving zero net energy use (ZNE) has developed into an established tool to meet globally accepted climate goals since its introduction in 2005. Even then, the urgency of the climate crisis– coupled with analysis of the opportunities for reducing emissions in buildings– led to a realization that we needed to reduce energy use in buildings to net zero by 2030.

Climate change is not something far away and in the remote future: it is here and now as these photos of melting glaciers and smoke from forest fires show. It is clear that we need ambitious action to reduce the impacts of the climate crisis. Getting buildings to ZNE is one such action on the path to mitigate the climate crisis.

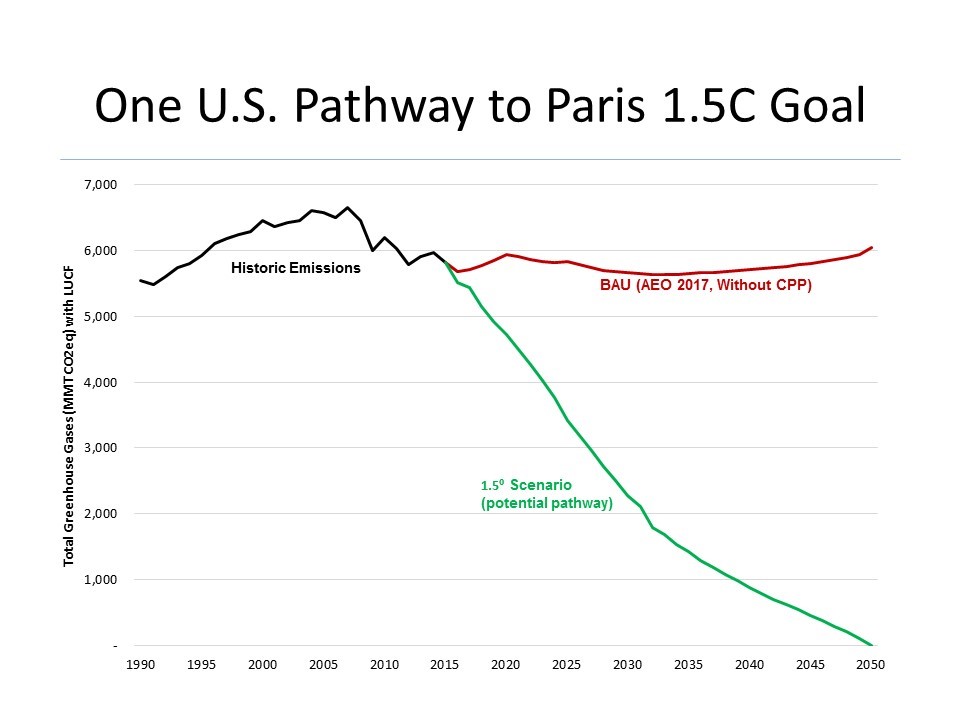

You can see the need for zero as a goal from the next figure. The impact on climate is given by the area under the curve. To keep that area, which represents cumulative emissions and thus the climate change impact, in line with the 1.5 degree curve, we must act boldly and we must act now.

But how do we get to zero? One way is to make use of another key tool for cutting climate pollution: Strategic Energy Management (SEM). This tool is complementary to the ZNE goal—and we believe that the two policies are strongly synergistic, as we presented to the ACEEE Summer Study (virtual) on Energy Efficiency in Buildings in August.

Starting with buildings

Since buildings account for some 35 percent of emissions throughout the developed world, ZNE buildings are a critical part of the global to-do list.

Fortunately, ZNE has attracted rapidly growing global interest. According to New Buildings Institute (NBI), growth rates of projected and verified ZNE projects continue to accelerate, as seen in their Getting to Zero buildings database. This progress has occurred despite a lack of incentives or mandates in most parts of the world. (In Korea, however, ZNE performance is required for public buildings as of 2020.)

Data from NBI and others show that Zero Energy buildings may not cost more to build than conventional practice, and they provide additional non-energy benefits such as comfort, health, etc.

Strategic Energy Management (SEM) as a tool for reducing emissions

SEM is a management process for controlling energy use. It requires an Energy Management System (EnMS) as a tool to yield continual improvement in energy performance. The EnMS requires:

- Top management approval of an energy policy

- An energy management team responsible for energy performance improvements

- Resources for the team can carry out the policy

- An energy planning process based on measured energy data

- Continuous review and adjustment of the policy to maintain performance improvements

SEM has achieved noteworthy success in facilities, despite the general lack of incentives for its use in the United States.

Synergy from Combining ZNE and SEM

These two policy concepts have complementary strengths and weaknesses.

ZNE sets an ambitious, measurable goal that can motivate building designers and operators to do more than they thought possible. But it doesn’t provide a process for getting there, nor does it continue promoting this high level of ambition by setting goals for improvement, rather than merely maintenance, of future performance.

SEM is solely based on process: its standards do not offer guidance on how much and how quickly energy performance is to be improved, but focuses on management procedures.

We can combine them by establishing the current ZNE goal as the metric for first-year measured performance of a building, and then add longer-term goals of higher levels of zero.

What is a “higher level of zero” and how can we get there?

When ZNE goals were first established, the level of performance was so much higher than normal that it was assumed that zero energy was the same as zero emissions. We now find that this is not true, based in part on the success of clean energy since the definition of ZNE was created.

Over the past decade, we found that solar energy, because it is produced by the building when everyone else was doing so as well, has become less valuable at reducing fossil fuel use. In regions with large-scale deployment of solar PV, power generation from those panels replaces less carbon-intensive generation than would have been the case if it were produced in the evening. This will be true more broadly as other jurisdictions establish ambitious goals for renewable energy.

Zero Net Carbon (ZNC), it became clear, was a more ambitious goal, and leading building designers and energy policy makers jumped to this goal to distinguish their projects from ZNE.

In response to this new reality, different versions of ZNC have been proposed by conference speakers at international meetings. These include zeroing out emissions from construction and the building materials themselves. A complete life cycle analysis (LCA) would also include transportation energy to get people and goods to and from the building, as well as other energy-intensive inputs such as water.

Integrating ZNE with SEM and constructing the ladder of ambition

While acceptance of ZNE is growing, it is still a niche market for new construction, and even less widely reached in existing buildings. Thus it would be counter-productive to “move the goal posts” by demanding ZNC across the board.

Yet leading designers are already building projects at ZNC and higher levels, and more and more organizations are advocating these levels. They deserve recognition for such achievements. Continual improvement through SEM can bridge the gap between ZNE and the higher levels of zero, including different flavors of ZNC that are described next.

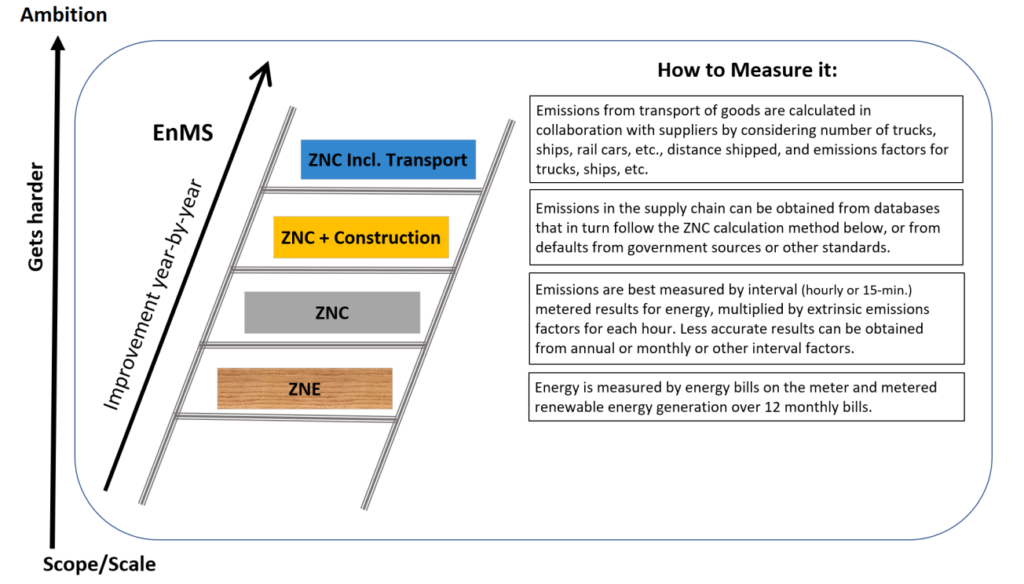

Our paper defines four ZNE/ZNC levels and suggests continual improvement from the lowest to highest levels:

- ZNE: offsetting the building energy use over the course of a year

- ZNC: offsetting the building’s emissions, taking into account the marginal energy inputs to the grid on a time-of-use (hourly) basis

- ZNC + Construction: considering, in addition to the emissions from operations , those required to construct the facility as well as the embodied emissions of the materials

- ZNC + Transportation: considering all of the above and in addition to the emissions from transportation of supplies and people to the site

The ladder rungs represent the four levels of ZNE/ZNC. The verticals represent the process of continual improvement through SEM, with specified goals to be met in planned future years. Note that SEM already requires the creation of an energy plan as part of its Energy Management System (EnMS) that spans several years, so this combination simply adds pre-specified quantitative goals to a process already required by SEM. An organization still has the latitude to decide when these more-ambitious goals will be met.

The ladder does not suggest the need for new ZNE standards, but instead represents a classification scheme for existing ideas.

Conclusion

The Zero Net Energy concept is an attractive way of making efficiency visible and for encouraging renewable energy use. It can be enhanced through the principle of continual improvement in SEM. The energy plan that SEM requires can allow an organization to set and reach higher ZNE goals at projected years in the future. These more ambitious goals are not easy–zeroing out construction energy and transportation requires far greater use of renewables. But such goals are already being discussed by leading architects and policy makers, and placing this discussion in the context of SEM may allow more projects to be considered feasible as multi-year efforts.

The International Organization for Standardization is developing a standard for zero net energy in operations that will try to incorporate these concepts into a guidance document for organizations interested in establishing and showing compliance with ZNE goals.