This blog was originally posted by NRDC on September 5, 2019.

Written by David Goldstein, Energy Co-Director, Climate & Clean Energy Program at NRDC.

Achieving Zero Net Energy (ZNE), which means that a facility produces as much renewable energy on- site as it consumes in a year, has been attracting rapidly increasing interest in the buildings context. But not as much attention has been paid to achieving ZNE in industrial facilities, which is a realistic goal for most of them. It should be pursued both to fight the climate crisis and to lower energy costs and make manufacturing more competitive.

The goal of this blog is to highlight the concept of ZNE for industry and show why it makes sense.

Leaders in the industrial sector are beginning to agree. Some are saying so directly but others are looking at the goal from a different perspective and arriving at a similar conclusion: they are committing their organizations to a goal of using 100 percent renewable energy at their manufacturing sites.

The reason for this interest is very clear:

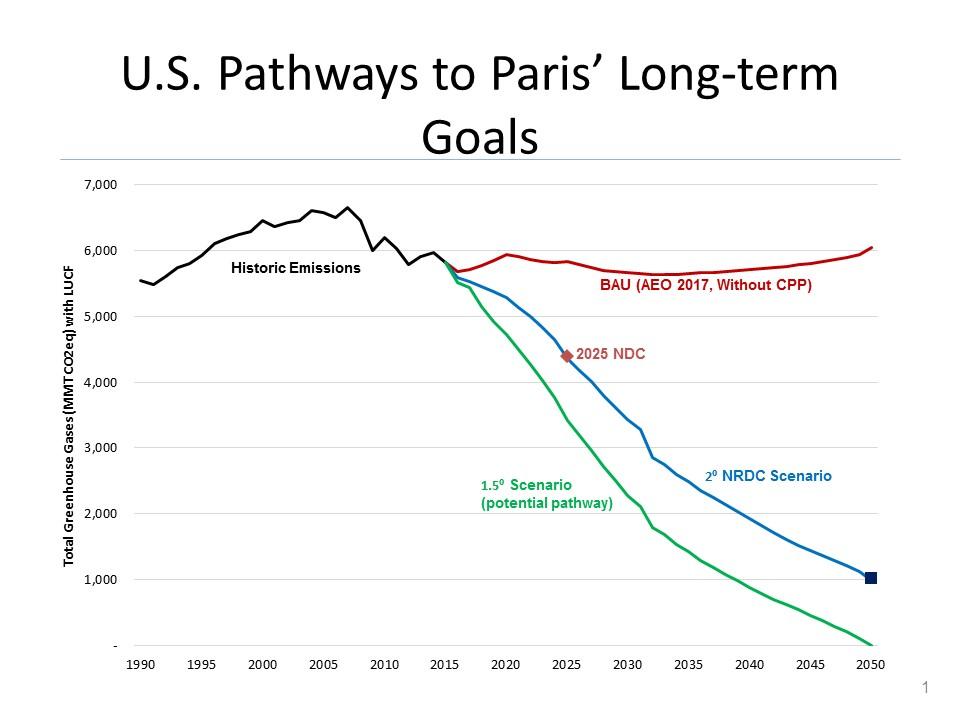

To meet the previous global goal of limiting the increase in global temperatures to 2 degrees C requires substantial reductions in emissions everywhere. For the U.S., emissions would need to drop by almost half by 2030. (Business as Usual (BAU) is seen as allowing emisisons to stay more or less constant.) Meeting this goal will pretty much require the buildings sector to approach ZNE over the next decade.

The Pre-Paris 2 C Goal Reaching the goal of keeping the increase in global temperatures to just 1.5 C goal requires a two-thirds or greater reduction by 2030. Even zeroing out the entire buildings sector is not enough.

Reaching the goal of keeping the increase in global temperatures to just 1.5 C goal requires a two-thirds or greater reduction by 2030. Even zeroing out the entire buildings sector is not enough.

So why not strive for ZNE in industry as well? My blog and paper on ZNE for industry look at criteria for combining ZNE with “Strategic Energy Management,” a technique that is more widely used in industry than anywhere else, and implicitly extends the scope of ZNE to include industry. In this blog I make that argument directly and explicitly: ZNE is a realistic goal for many industrial facilities, and a plausible long-term ambition for most plants.

The only argument against this position has been to note that industry is much more energy intensive than commercial buildings or homes, and so there isn’t enough land area to generate renewable energy for ZNE industry (ignoring the fact that ZNE for a 40-story downtown building or a ten-story urban hospital is also comparably challenging.)

Let’s look at this quantitatively. A Google search of industrial land area shows some 11 million acres of industrial land in the lower 48 states (this includes manufacturing but not agriculture, fishing, or forestry). If we covered them all with solar photovoltaic panels and ignored wind potential, we could generate about 30 quads of energy. This is roughly equal to the energy consumption of industry as a whole.

Thus in aggregate, ZNE for industry is possible. There are several examples of ZNE facilities that can be seen on the Internet, and one of them is in the NBI ZNE data set. We will probably find a lot more when we begin to collect data on them systematically.

I’m not necessarily suggesting that we need to cover 11 million acres in PV panels. With improved energy efficiency that results from a ZNE goal, the land requirements are lower.

And while ZNE standards prefer on-site renewable generation, most standards worldwide allow some methods of counting offsite generation (but usually with a discount factor), especially if it is dedicated to the facility in question. It follows that ZNE is a plausible goal for most, or at least many, sites.

Indeed, some (or perhaps many) ZNE industrial plants already exist, but they are not being tracked or written about so we don’t know the numbers.

Buildings and industrial plants account for over two-thirds of climate emissions in most countries. If these facilities comply with ZNE goals, emissions reductions will be much easier. When buildings and industrial plants generate their own energy via wind and solar, for example, that avoids the need for central powerplants to generate electricity to run them—and avoids the climate-warming pollution that comes with that power generation. It’s also cheaper.

ZNE vs. 100 Percent Renewable Energy

How realistic are ZNE goals? As noted earlier, many large companies already are committing to 100 percent renewable energy. ZNE is one way that achieves the goal, by its very definition. But it also offers more flexibility and spurs more creativity to improve performance, and thus more jobs to implement the creative work. And in addition, it is greener because we can be more assured that the renewables would not have been built otherwise and because ZNE is likely to lead to much more investment in energy efficiency so the renewable energy can stretch further.

A goal of 100 percent renewables without reference to the plant’s energy performance, though, produces less benefit. This goal can be achieved merely by writing contracts and signing checks.

This would place heavy reliance on “renewable energy credits,” which most standards on ZNE prohibit or discount because they may be for off-site energy that may not even be possible to deliver to the site. There is a strong consistency in ZNE standards worldwide to minimize reliance on such credits: Many people have expressed deep skepticism about the ethics of credits, including Pope Francis.

“… credits” can lead to a new form of speculation which would not help reduce the emission of polluting gases worldwide. This system seems to provide a quick and easy solution under the guise of a certain commitment to the environment, but in no way does it allow for the radical change which present circumstances require. Rather, it may simply become a ploy which permits maintaining the excessive consumption of some countries and sectors.”

Regardless of whether you agree, ZNE goals can be achieved by eliminating “excessive consumption” at a facility through process changes, efficiency upgrades, and maintenance improvements that often offer other benefits in terms of productivity and product quality and usually cost less than leaving things as they were. This makes it easier to achieve the renewable energy goal and bypasses any ethical concerns. (There are also practical concerns with the use of renewable energy credits for ZNE compliance, focused on whether the renewables in question would have been built even without the facility ZNE commitment.)

In my paper, I propose that ZNE (particularly ZNE emissions—a much more important but difficult goal, as the paper explains), also suggests a commitment to continually improve energy efficiency and energy/emissions performance. One-off environmental commitments are less transformational than ongoing policies.

Solving the climate problem offers large benefits to individual companies, as well as to society at large. Policies such as ZNE and continual improvement allow companies to strive for and take credit for significant environmental achievements and to satisfy other business goals at the same time. Combining these two ideas helps put us on track to meet the world’s ambitious climate change reduction goals.

Note: The Paris Agreement does not call out the NUMBER 1.8 degrees. Instead its goal is “well under 2 degrees”. But let’s use some common sense: most people would not consider 1.9 to be “well under” 2. But I think 1.8 would qualify.